Rewriting moderndescartes.com as a static site

Originally posted 2018-03-10

Tagged: software engineering

Obligatory disclaimer: all opinions are mine and not of my employer

(This was originally a talk given at Hack && Tell Boston.)

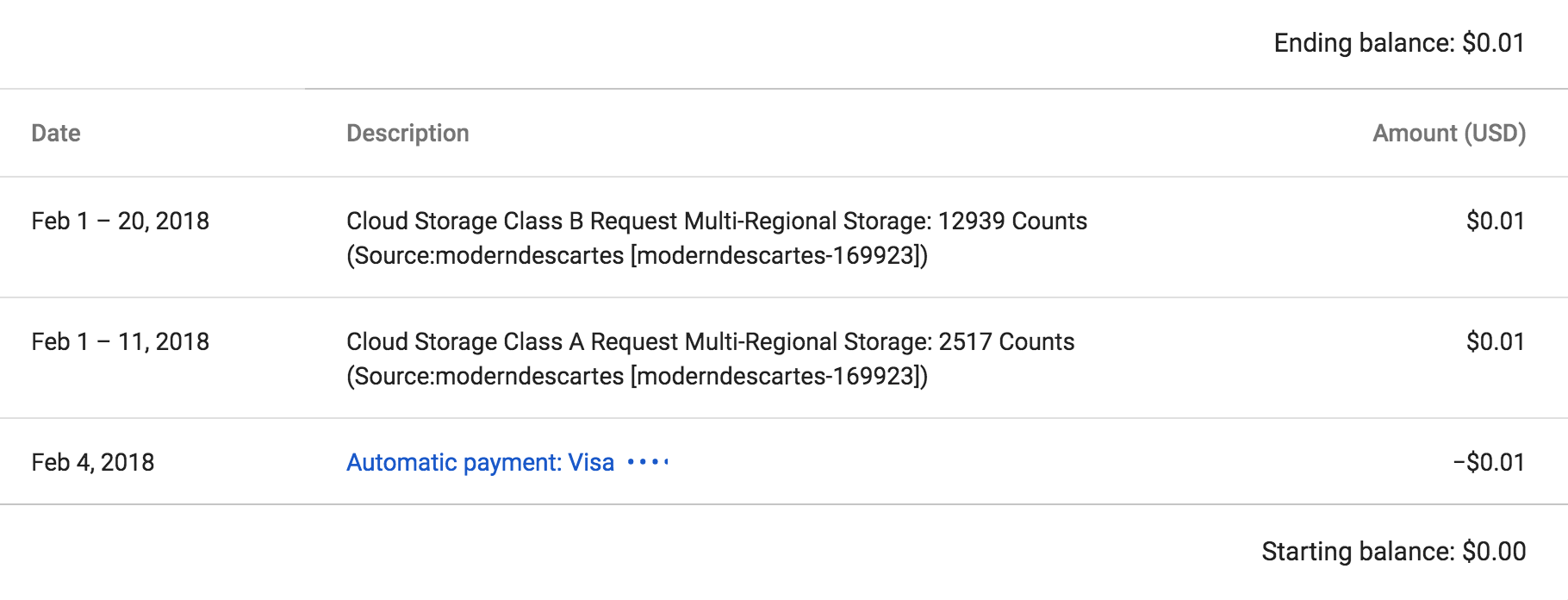

You may or may not have noticed that my website is now being served from Google Cloud Storage. If you haven’t, great! My wallet, on the other hand, has definitely noticed:

Read on for a quick rundown of how I went about converting my website.

What’s a static site?

First, let’s clear up the difference between a static and a dynamic site.

google.com is your prototypical dynamic site: it takes your query, your login status, location, and lots of other things to decide what results to return. It then puts together a HTML page which it sends back to your browser to be displayed. Chances are, this exact HTML has never been sent to anybody else before.

A static site, on the other hand, sends the same HTML file to everyone. Because it is so simple to serve static files, many services will host files for you, like content delivery networks, or in my case, Google Cloud Storage.

A blast from the past

The previous backend for this website was a Django 1.4 instance. I hadn’t upgraded it in almost 6 years - Django 1.4 was originally released in March 2012! There was also a MySQL server, and who knows what security holes there were in the whole thing. Compiling new essays relied on an ancient python MarkDown library that I could no longer find on PyPI. To add insult to injury, I paid $80/year for the privilege of maintaining this tire fire of a website backend.

The breaking point was when I got a new laptop and was unable to reinstall the python MarkDown library, which meant that I couldn’t render/view my essays locally before pushing them live.

Compiling static pages

The first order of business was finding a replacement MarkDown compiler. I first started with a handful of python libraries, but none of them could handle hybrid MarkDown/LaTeX documents. I then remembered that Pandoc existed, and just like that, all of my problems were magically solved.

So, to recompile all of my webpages, I passed the raw MarkDown essays through Pandoc, and then through jinja2 (a Django compatible templating engine) to compile the webpages as they had previously been rendered on my website.

For static assets, nothing more than a cp -r was

needed.

For my RSS feed, I used a standalone version of Django’s RSS feed generator. Technically, RSS feeds are dynamic, but they only ever change when a new essay is posted, so I could simply recompile it each time I pushed a new essay.

Everything went into a staging directory, after which a single

command deploys the whole thing:

gsutil -m rsync -r -d staging gs://www.moderndescartes.com.

Hiccups with the new GCS static site

As it turns out, having a static site doesn’t just mean serving files, but also correctly setting various HTTP headers on the responses. For example, I had to figure out how to get GCS to put a content-type:text/html header on my extensionless files. I also ended up having to add <meta charset=“utf-8”/> to my pages, because this was something Django had transparently handled for me before.

I also discovered that cp -p would preserve modification

times, which meant that I could prevent gsutil rsync from

attempting to reupload my entire static directory everytime I recompiled

my files.

There was an unfruitful detour into gzip-land;

gsutil cp -z would apparently gzip files automatically

before uploading them, and would even automatically set the

content-encoding property, so that the pages would be served correctly.

But gsutil rsync didn’t support this flag, so instead of

maintaining a weird hybrid push step of gsutil cp for my

HTML pages and gsutil rsync for my static assets, I

abandoned the idea altogether.

Conclusion

Writing my own static site compiler has been remarkably easy to do. In between jinja2 templating and Pandoc for correctly compiling MarkDown/LaTeX files, I’ve ended up with 100 lines of Python that replace the entire Django installation I used to have. The initial prototype took me 3 hours on a plane to write; cleaning up the push/deploy process took another few hours of futzing around with gsutil doc pages.

To take a peek at the code supporting this static site, check out the Git repo.

Update 11/17/2019

I moved over to Firebase hosting, because it supports SSL, and the GCS static site hosting did not. Firebase hosting has been quite simple and I haven’t run into any of the hiccups I previously encountered.