The FactoBattery

Originally posted 2023-01-03

Tagged: sustainability, popular ⭐️

Obligatory disclaimer: all opinions are mine and not of my employer

Renewable energies are very annoying to grid operators. Their energy production is unreliable, yet the grid requires that energy production and consumption be matched instantaneously. As a result, backup grid capacity (typically, fossil fuels) is required in proportion to the amount of renewables. At other times, renewable energy is sometimes curtailed, which is to say, “temporarily disconnected to avoid overenergizing the grid”. Grid operators are accustomed to dealing with some variation, and curtailment rates are currently low, around 5%. But as renewables continue to grow, 25% curtailment is our likely future.

The obvious answer is to just build a lot of batteries. But where’s the fun in that? How about using curtailed energy to synthesize methanol/fertilizer/aviation fuel, capture CO2, and so on? Unfortunately, these are effectively suggestions for batteries (if I may, “factobattery”), and if compared to actual batteries, turn out to be not very cost-effective. That is to say, once you’ve built the factory, you would rather pay for grid electricity and run 24/7, rather than run on free electricity for a disappointingly low 25% utilization rate.

Unfortunately, we can’t all rely on the grid! Somebody has to figure out the grid balancing problem. I present here a methodology for evaluating various factobatteries for their utility as batteries. The good news is that some factobatteries make financial sense.

The Nature of the Beast

Grid balancing occurs at many timescales.

At the finest level, it consists of the tiny surges and dips in demand, every time somebody flips a light switch. These sorts of fluctuations are automatically accommodated by the sheer physical momentum of thousands of electrocoupled steam turbines, as well as giant capacitor banks to instantaneously provide extra power when it’s needed. Occasionally, manual intervention is needed when these surges and dips are correlated - e.g. during TV breaks for especially popular programs.

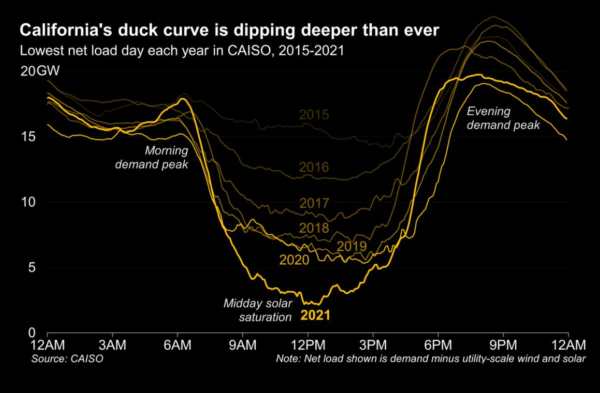

On a day’s timescale, power usage mostly follows standard office hours, rising in the morning and peaking in the evening. Fortunately, this mostly aligns with solar output (except evenings), so solar power is a great complement to the daily rhythm of life. Subtracting the solar curve from the demand curve results in the so-called “duck curve”. One logical idea which I haven’t seen discussed is pairing each region with solar panels to their west.

During those evening peaks, a mix of pumped water storage and peaker plants operate on an as-needed basis to balance the grid. Peak energy is far more expensive, as the fixed capital costs of a power plant must be recouped over a much shorter operational period.

Over a year’s timescale, we have the seasons. The spring and fall are most moderate in their energy needs, while the summer months require air conditioning and the winter months require heating. In my home region of New England, giant LNG tankers float offshore through the winter, piping natural gas into homes and power plants to help offset this energy imbalance.

There are also weekend, holiday, and bad weather scenarios. Even El Niño/La Niña affect reservoirs and thus hydroelectric power over years-long periods.

Batteries move energy through time

The obvious solution to grid balancing is to add batteries to the grid. To compare batteries, we can look at a few key parameters.

- Charge/Discharge rate

- Capacity (how long it can maintain the discharge rate)

- Response time (how much lead time is needed to access stored energy?)

- Lifetime (how many charge/discharge cycles)

- Cost

When asking what the “best” battery is, one must first define “best”. Capacitors are great for grid balancing millisecond-level fluctuations, but has far too small of a capacity for any longer-term fluctuations. On the other hand, pumped water storage, with large capacity and a response time of 10 minutes, is ideal for daily grid balancing. The demand curve (daily + weekly + seasonal + holiday + weather + surges) requires a mix of strategies to address each type of grid imbalance.

In my opinion, daily grid balancing presents the biggest opportunity, as solar generation is likely to continue scaling up. Solar energy will overwhelm the daytime peak, requiring correction in the opposite direction.

Let’s analyze the suitability of batteries for this scenario. I will assess batteries on their ability to harness excess solar energy for 1/4 of the day and release that energy for 3/4 of the day. This is the opposite of what is normally assumed! Usually we assume overnight energy is cheap and that daytime energy is expensive. But it’s what the future holds for us. In California where solar is already pervasive, it’s the present.

In this scenario, a conventional lithium-ion battery has the following stats:

| Technology | Lifetime | Capex | Rate | Capex/y | Opex/y | Fuel | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li battery | 10 years | $522M | 8% | $76M | $1M | 0 | $77M |

To make all of our batteries comparable, everything is scaled to 100MW. For a conventional battery, this means a daily cycle of 300MW charging for 6 hours followed by 100MW discharge for 18 hours (a total of 1.8GWh of capacity). I normalize for varying lifetimes by annualizing capital borrowing costs. $516M at an 8% annual interest rate over 10 years gives a yearly capex of 75M dollars. (Think of it as a really big mortgage.)

Some less conventional batteries

If batteries move energy through time, peaker plants move energy production through time. Both are levers to balance the grid. A peaker plant is therefore in some sense a battery. Other programs, like residential incentive programs, are also “batteries”. This idea goes by the names “virtual power plant”, “demand response”, and “curtailment provider”.

| Technology | Lifetime | Capex | Rate | Capex/y | Opex/y | Fuel | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li battery | 10 years | $522M | 8% | $76M | $1M | 0 | $77M |

| Natural Gas peaker | 40 years | $125M | 5% | $7M | $4M | $17M | $28M |

| Residental curtailment | 5 years | $180M | 8% | $43M | $33M | 0 | $76M |

You’ll note I applied a more favorable interest rate to the peaker plant. This reflects the maturity of the technology, the maturity of the product-market fit, and overall lower risk on the investment. See this chart for interest rate variations by industry, which is stale (it predates interest rate bumps in 2022) but instructive. The peaker plant is the benchmark to beat if you want to win without subsidies/carbon taxes.

I also modeled a residential curtailment program, but it’s hard to get the numbers to work - the effort required to sign up customers, and the incentives you would have to dangle, make this solution not very cost-effective. A passively managed dual-rate program would be more cost-effective, even if the uptake wasn’t high. Industrial/commercial curtailment programs would also be more cost-effective.

The Factobattery

This brings us to the factobattery. The idea is simple: take a factory whose primary input is electricity, and overbuild it by 4x. Run it at 4x capacity during daylight and turn it off at night. Overall, this 4x factobattery is indistinguishable from a 1X factory in terms of its output. The “battery equivalent cost” is then 3x the factory cost.

One example is an aluminum smelter, which consumes electricity to electrolyze aluminum oxide/carbon into aluminum metal and carbon dioxide. I picked aluminum smelting as an example because it’s responsible for something like 3-5% of worldwide electricity consumption, but it turns out to be a very bad factobattery.

Another more favorable example is an electrolysis-driven fertilizer plant. In this scheme, electricity is used to generate hydrogen gas, which is combined with nitrogen using the Haber-Bosch process to form ammonia. Note that this is an emerging technology (nearly all HB uses methane-derived hydrogen gas) and thus gets a harsher interest rate.

| Technology | Lifetime | Capex | Rate | Capex/y | Opex/y | Fuel | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li battery | 10 years | $522M | 8% | $76M | $1M | 0 | $77M |

| Natural Gas peaker | 40 years | $125M | 5% | $7M | $4M | $17M | $28M |

| Residental curtailment | 5 years | $180M | 8% | $43M | $33M | 0 | $76M |

| Aluminum smelting | 8 years | $1000M | 5% | $151M | $200M | 0 | $351M |

| Electrolysis/HB plant | 8/30 years | $360M / 300M | 8% | $21M + 27M | $17M | 0 | $65M |

It turns out that overbuilding a plant by 3x is expensive and wasteful and if you don’t actually use it.

Minimizing the overbuild

Actually, the fertilizer plant doesn’t have to be overbuilt in its entirety. Instead, we merely have to overbuild the electrolyzers at 4X, install some hydrogen buffering capacity, and the downstream Haber-Bosch unit, built at 1X, can run at 100% utilization. The net cost of this factobattery is much cheaper:

| Technology | Lifetime | Capex | Rate | Capex/y | Opex/y | Fuel | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li battery | 10 years | $522M | 8% | $76M | $1M | 0 | $77M |

| Natural Gas peaker | 40 years | $125M | 5% | $7M | $4M | $17M | $28M |

| Residental curtailment | 5 years | $180M | 8% | $43M | $33M | 0 | $76M |

| Aluminum smelting | 8 years | $1000M | 5% | $151M | $200M | 0 | $351M |

| Electrolysis/HB plant | 8/30 years | $360M / 300M | 8% | $21M + 27M | $17M | 0 | $65M |

| Electrolysis/H2 buffer | 8/25 years | $360M / 20M | 8% | $21M + 2M | $5M | 0 | $28M |

In this analysis, overbuilt electrolysis is a third as expensive as lithium-ion batteries, and comparable to peaker plants in cost! Yet, this does not imply that it is economically worthwhile to build an electrolysis-fed Haber Bosch plant. It merely says that, if you’re already building an electrolysis-fed Haber-Bosch plant, then you could overbuild its electrolyzers and provide competitive battery services.

This synergy probably pushes the electrolysis/H2 storage/HB combo into “competitive even without subsidies” territory.

Sidenote: Hydrogen Economy?

Actually, there’s nothing special about the Haber-Bosch unit on the receiving end of this electrolysis setup. The same trick could be applied to any consumer of hydrogen gas. Currently, major consumers of hydrogen gas are fertilizer and methanol production. Hydrogen gas is also used for desulfurization and cracking of petroleum products, but it seems unlikely that these use cases will switch to electrolysis-generated hydrogen (why pay for electricity when you have abundant petrochemical-derived hydrogen on-site?). Fertilizer and methanol production will likely switch to electrolysis first, providing an opportunity to create factobatteries. The next lowest hanging fruit is probably hydrogen steelmaking, although this is still an emerging technology.

Proponents of the hydrogen economy talk about many other uses for hydrogen, like fuel cells, power plants, transportation, etc.. I think most of these ideas are silly (and this guy agrees). Hydrogen gas is just not dense enough of a physical material to be worth transporting, and you incur heavy conversion losses when turning it back into electricity.

The electrolysis/hydrogen buffering factobattery works well because the hydrogen is directly consumed in a downstream industrial process. This means we don’t need to transport hydrogen, we don’t need fuel cells to recover the energy, and we only suffer conversion losses of electricity <-> hydrogen once, not twice.

Conclusion

I believe that buffered hydrogen electrolysis with onsite consumption is a promising way to take advantage of curtailed renewables, surpassing lithium batteries in cost efficiency.

I was surprised at lithium batteries’ mediocre performance. On second thought, it makes sense - my evaluation methodology is probably not the scenario these lithium batteries are designed for. Rather, their rapid response capabilities are more suited to unexpected demand or peak demand scenarios, not daily balancing. Still, as many grid operators are announcing lithium battery sites, it seems that anything that beats a lithium battery is worth looking into. Of course, there are many potential batteries that I haven’t analyzed, and there might be something even better out there.

The biggest lesson in this is that “free” energy is not really free. You need to build the machines that will consume that energy, and they are often expensive enough that free energy isn’t enough of an incentive.

Citations

All sizing calculations are done with respect to electricity consumption, regardless of downstream efficiency/conversion losses. This is because we only care about the load from the grid’s perspective.

Lithium battery: Section 18/19 of this AEO 2020 report provides numbers for a 200MWh capacity/50MW discharge (\(x =\) 69M) and 100MWh capacity/50MW discharge (\(y =\) 42M). \(10x - 4y\) = 522M gives numbers for a 1800 MWh capacity and 300MW charge/discharge rate. A daily discharge/charge cycle is assumed. You can tell that I’m not using the batteries correctly because literally everybody assumes a trickle charge and rapid discharge, but I actually want a rapid charge over 6 hours followed by a trickle discharge.

Peaker plant: A natural gas simple cycle plant is assumed. Section 5 of same AEO 2020 report gives these numbers. Note that “simple cycle” is the simplest type of gas plant and is not particularly efficient. It’s just the lowest capital cost/highest fuel cost, which suits peaker plants. Arguably, a plant operating 75% of the time should use a more efficient design. But more efficient designs also tend to come with burdensome startup/shutdown routines, unsuitable for daily power cycling.

Residential curtailment program: Just some wild estimates. I’m assuming that for a Customer Aquisition Cost (CAC) of $100/person (marketing, smart device, etc.), you can convince a household to move 1kWh worth of time-insensitive workloads to midday hours. To accumulate 1.8 GWh of curtailment capacity, you then need 1.8M customers, for a total capex/CAC of 180M. I assume customers will churn in 5 years. The customer would likely want half of the energy savings back, for an opex of roughly 5 cents/kWh * 1.8 GWh/day * 365 days = 33M/year.

Aluminum smelting: Assuming 15 kWh per kg of aluminum, a 100MW capacity plant is equivalent to 67 kT/year in aluminum smelting capacity. According to ETSAP 1012, aluminum smelters costs ~$5000 / annual ton capacity. Total cap cost is then 330M over a cathode lifetime of 8 years. Opex is given as ~$1000 / annual ton capacity. I ignore the costs of bauxite/anodes/cryolite/etc. since these are stoichiometric with the factory’s output, which is still 1x. I also ignore the cost of maintaining the cell temperature, which is generous (the cell would cool down while not being used, and additional energy is needed to heat it back up).

Haber-Bosch synloop cost: Table 12 of Bartels 2008

Electrolysis: PEM electrolysis is assumed. According to this CATF report, a 2020 100MW PEM electrolysis configuration costs 72M with project-dependent land / supplier markups - let’s estimate 120M total. The annuitized cost calculation is more complicated PEM units have a lifetime of 40-70,000 operating hours. Running at lower utilization means longer lifetime; the annuitized cost is then (120M * 4 over 32 years) - (120M over 8 years), the difference between a 4X factobattery and a 1X factory.

H2 storage: A buried pipe H2 storage system is assumed ($20M over 25 years), since salt caverns are too large for this use case and would add geographic constraints. Although I assume 1 days’ buffering, more than 1 days’ storage would be needed, since it can be cloudy for many days in a row, and it’s cheaper to overbuild hydrogen storage than to idle your Haber-Bosch reactor. Estimates from HyUnder report and Papadias 2021

Other Caveats

Going through this exercise, there are a lot of key assumptions being made.

- I assume solar cells will continue to drop in price, leading to…

- continued growth of the solar industry, causing a significant duck-curve imbalance…

- reaching rates of 25% curtailment over the next 5-10 years. If we don’t hit these curtailment numbers, the factobattery multipliers get worse - 20% curtailment requires 5x overbuild, and so on.

- I’m not sure investers will be sympathetic to this Frankenstein of an investment thesis. One set of investors may be excited to invest in green ammonia (exciting!), and another set of investors may be excited to invest in grid battery storage (boring?), but a factobattery requires these two sets to overlap.

- My analysis is with 2020 price points. Prices of various components (electrolyzers, solar, hydrogen storage) are constantly dropping, but I do expect this to only help my argument.