Harmonic Curiosities

Originally posted 2012-02-03

Tagged: music

Obligatory disclaimer: all opinions are mine and not of my employer

This analysis assumes that you have some background in music theory. It also helps if you are sitting at a piano while reading this, so that you can play the indicated chords.

Part 0: A Brief Introduction to Harmonic Analysis

You may have learned in your counterpoint lessons that different voices should move in opposite motion, either inwards or outwards. Opposite motion strongly creates the sensation of distinct voices, and this is an integral part of “correct” voice leading. In sections where parallel thirds or sixths are used, this sensation is weakened, although not eliminated. When voices fall into (gasp) parallel fifths or parallel octaves, this multi-voice sensation will suddenly collapse, causing the music to sound sparse and jarring.

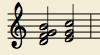

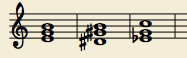

The simplest example of opposite motion in voice leading is the

movement from dominant seventh to tonic (V43 -> I6).

There is one strongly dissonant interval, a tritone, which resolves

outward from F/B to E/C. The D and G in the dominant seventh serve to

harmonize and connect the two chords, and are in fact unnecessary to

hear the chord resolution. (Try playing only F/B to E/C).

There is one strongly dissonant interval, a tritone, which resolves

outward from F/B to E/C. The D and G in the dominant seventh serve to

harmonize and connect the two chords, and are in fact unnecessary to

hear the chord resolution. (Try playing only F/B to E/C).

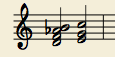

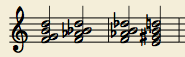

A slightly more complex

example of opposite motion is the resolution of a diminished chord to a

major chord (vii65o -> I6). Only one note has changed from the

previous example, creating a second tritone interwoven with the first.

Each of these tritones resolves by opposite motion - D/Ab resolves

inwards to E/G; F/B resolves to E/C.

example of opposite motion is the resolution of a diminished chord to a

major chord (vii65o -> I6). Only one note has changed from the

previous example, creating a second tritone interwoven with the first.

Each of these tritones resolves by opposite motion - D/Ab resolves

inwards to E/G; F/B resolves to E/C.

An even more complex example is the resolution of an augmented sixth

chord.

(The following chord progression sets up the augmented sixth; this one’s

harder to hear in isolation.) The Ab and F# are strongly dissonant, and

they resolve outwards to an octave G.

(The following chord progression sets up the augmented sixth; this one’s

harder to hear in isolation.) The Ab and F# are strongly dissonant, and

they resolve outwards to an octave G.

In the classroom, these harmonic progressions are usually presented in a functional manner (pre-dominant -> dominant -> tonic), but I have instead presented this material in terms of voice leading and resolving dissonances. I prefer this second way, because it is more general and capable of handling unusual harmonies, such as those used by Rachmaninoff, Barber, and Poulenc. I’ll be using this method of analysis throughout this essay.

Now, the real fun begins.

Part 1: Major Third Shifts

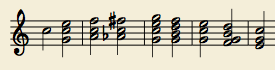

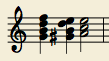

Consider the following three chords.

These three chords have the interesting property that any one chord can

resolve to another chord. You may have noticed that they trace out C, E

and Ab major chords - three chords, spaced apart by a major third.

Therefore, I will call this chord change a major third shift, or M3

shift. (In textbooks, it’s often called a common-tone modulation, but an

M3 shift doesn’t necessarily require a modulation.) The M3 shift can

quickly and subtly transform the piece, and before you know it, you’re

in another universe.

These three chords have the interesting property that any one chord can

resolve to another chord. You may have noticed that they trace out C, E

and Ab major chords - three chords, spaced apart by a major third.

Therefore, I will call this chord change a major third shift, or M3

shift. (In textbooks, it’s often called a common-tone modulation, but an

M3 shift doesn’t necessarily require a modulation.) The M3 shift can

quickly and subtly transform the piece, and before you know it, you’re

in another universe.

Here’s the M3 shift in Wagner’s Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde (piano transcription by Liszt). No timestamps; M3 shifts happen almost every measure.

How does this M3 shift work? First, there is one common tone in each of the transformation - this is the tone that is held, and typically the one that is emphasized, while everything else around it changes. Second, the two chords are of equal consonance/dissonance - neither is of a higher musical tension than the other, so the M3 shift doesn’t feel like it’s either resolving or building tension. Thus, the M3 shift can be navigated in either direction. Finally, as with the examples from the introduction, voices “resolve” in opposite directions. I say “resolve” with scare quotes, because there is no dissonance to be resolved. A perfectly consonant perfect fourth moves inwards to a minor third (and vice versa).

The M3 shift also works with minor chords:

The principles are much the same, but when used on minor chords, the tension seems to build with each shift. Here it is in action:

Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G, 2nd mvmt; m3 shift from Em/B -> G#m/B occurs at 6:44

In summary: the M3 shift links the chords sets [C, E, Ab], [Db, F, A], [D, F#, Bb], and [Eb, G, B], both as major and minor triads.

Part 2: Minor Third Shifts

M3 shifts have many symmetries - 3 notes in a chord; 3 chords in each set, movement by a major third = 4 half steps; 4 sets of chords; 3*4 = 12 scale degrees in the octave.

When presented with these numbers, it becomes obvious that other kinds of shifts should exist. Without even constructing the relevant chords, we can predict that the minor third (or m3) shift will have these symmetries: 4 notes in a chord; 4 chords in each set, movement by m3 = 3 half steps; and 3 sets of chords. (If you’re wondering, the 2/6, 6/2, 1/12 and 12/1 cases aren’t very harmonically interesting.)

But what are the four notes of our chords? The M3 shift was usable with both major and minor chords. It turns out that dominant, minor, and half-diminished seventh chords are all amenable to the m3 shift. The dominant seventh version seems to be most commonly used, while the other possibilities are less commonly used.

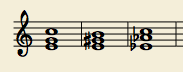

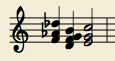

Consider the following four chords.

As with the chords in the M3 shift, these four chords have the property

that any chord can resolve to any other chord. They are also equally

spaced around the octave, tracing out [G, Bb, Db, E] seventh chords. You

can walk through these chords by “resolving” a major third inwards to a

major second, or vice versa. You can also jump to the chord that’s a

tritone away, by “resolving” a perfect fifth inwards to a perfect

fourth, and vice versa.

As with the chords in the M3 shift, these four chords have the property

that any chord can resolve to any other chord. They are also equally

spaced around the octave, tracing out [G, Bb, Db, E] seventh chords. You

can walk through these chords by “resolving” a major third inwards to a

major second, or vice versa. You can also jump to the chord that’s a

tritone away, by “resolving” a perfect fifth inwards to a perfect

fourth, and vice versa.

m3 shifts are actually quite common in Classical era music, although I

wonder if composers of the day realized the full mathematical generality

of the chords they were using. For example, the following harmonic

progression (a modulation to the relative minor) sounds so normal that

it’s only with large leaps of abstraction that I can call it an “m3

shift”.

m3 shifts are actually quite common in Classical era music, although I

wonder if composers of the day realized the full mathematical generality

of the chords they were using. For example, the following harmonic

progression (a modulation to the relative minor) sounds so normal that

it’s only with large leaps of abstraction that I can call it an “m3

shift”.

Another m3 shift used by Classical era composers is the Neapolitan

chord.

As illustrated, the Neapolitan usually resolves to the dominant, which

is an entire tritone away. Since most classical music consists of

harmonic movements of a perfect fifth, or other consonant intervals, the

Neapolitan chord breaks from this tradition strongly, and at first,

seems to operate by magic. The Neapolitan is usually explained as a

variant on a IV chord (the Neapolitan is a M3 shift away from IV), but

you can also see it as a m3 shift to V7. I’ve notated the chord without

the seventh, which you’ll find is often omitted in m3 shifts.

As illustrated, the Neapolitan usually resolves to the dominant, which

is an entire tritone away. Since most classical music consists of

harmonic movements of a perfect fifth, or other consonant intervals, the

Neapolitan chord breaks from this tradition strongly, and at first,

seems to operate by magic. The Neapolitan is usually explained as a

variant on a IV chord (the Neapolitan is a M3 shift away from IV), but

you can also see it as a m3 shift to V7. I’ve notated the chord without

the seventh, which you’ll find is often omitted in m3 shifts.

The previous two examples are subtle m3 shifts. Here are two examples where the m3 shift is used more nakedly:

Chopin Prelude op. 28, no. 17, m3 shifts occur at 1:14, 1:20-1:24, 1:27

Faure Requiem, Agnus Dei; a sequence using m3 shifts occurs at 2:14

In summary: the m3 shift links [C, Eb, F#, A], [C#, E, G, Bb], [D, F, Ab, B] dominant seventh chords.

The chords here are a small offering from the world of classical music. Almost all modern pop music descends in some way from classical music, so if you find yourself appreciating music in any way, I encourage you to dig deeper into the old stuff!