Using Linear Counting, LogLog, and HyperLogLog to Estimate Cardinality

2016-12-04

Tagged: software engineering, math

Introduction

Cardinality estimation algorithms answer the following question: in a large list or stream of items, how many unique items are there? One simple application is in counting unique visitors to a website.

The simplest possible implementation uses a set to weed out multiple occurrences of the same item:

def compute_cardinality(items):

return len(set(items))Sets are typically implemented as hash tables, and as such, the size of the hash table will be proportional to the number of unique items, \(N\), contained within it. This solution takes \(O(N)\) time and \(O(N)\) space.

Can we do better? We can, if we relax the requirement that our answer be exact! After all, who really cares if you have 17,000 unique IPs or 17,001 unique IPs visiting your website?

I’ll talk about Linear Counting and LogLog, two simple algorithms for estimating cardinality. HyperLogLog then improves on LogLog by reusing ideas from Linear Counting at very low and very high load factors.

Linear Counting

Sets are inefficient because of their strict correctness guarantees. When two items hash to the same location within the hash table, you’d need some way to decide whether the two items were actually the same, or merely a hash collision. This typically means storing the original item and performing a full equality comparison whenever a hash collision occurs.

Linear Counting instead embraces hash collisions, and doesn’t bother storing the original items. Instead, it allocates a hash table with capacity B bits, where B is the same scale as N, and initializes the bits to 0. When an item comes in, it’s hashed, and the corresponding bit in the table is flipped to 1. By relying on hashes, deduplication of identical items is naturally handled. Linear Counting is still \(O(N)\) in both space and time, but is about 100 times more efficient than the set solution, using only 1 bit per slot, while the set solution uses 64 bits for a pointer, plus the size of the item itself.

When \(N \ll B\), then collisions are infrequent, and the number of bits set to 1 is a pretty good estimate of the cardinality.

When \(N \approx B\), collisions are inevitable. But the trick is that by looking at how full the hash table is, you can estimate how many collisions there should have been, and extrapolate back to \(N\). (Warning: this extrapolation only works if hash function outputs suitably random bits!)

When \(N \gg B\), every bit will be set to 1, and you won’t be able to estimate \(N\).

How can we extrapolate the table occupancy back to \(N\)? Let’s call the expected fraction of empty slots after \(n\) unique items \(p_n\). When adding the \(n+1\)th unique item to this hash table, with probability \(p_n\), a new slot is occupied, and with probability \((1-p_n)\), a collision occurs. If you write this equation and simplify, you end up with \(p_{n+1} = p_n (1 - 1/B)\). Since \(p_0 = 1\), we have \(p_N = (1 - 1/B)^N\).

Solving this equation for \(N\), we end up with our extrapolation relationship:

\[N = \frac{\log p_N}{\log (1 - 1/B)} \approx -B\log p_N\]

where the second approximation comes from the first term of the Taylor expansion \(\log(1 + x) = x - x^2 / 2 + x^3 / 3 - x^4 / 4 \ldots\).

This is a very simple algorithm. The biggest problem with this approach is that you need to know roughly how big \(N\) is ahead of time so that you can allocate an appropriately sized hash table. The size of the hash table is typically chosen such that the load factor, \(N/B\) is between 2 to 10.

LogLog

LogLog uses the following technique: count the number of leading zeros in the hashed item, then keep track of the max leading zeros seen so far. Intuitively, if a hash function outputs random bits, then the probability of getting \(k\) leading zeros is about \(2^{-k}\). On average, you’ll need to process ~32 items before you see one with 5 leading zeros, and ~1024 items before you see one with 10 leading zeros. If the most leading zeros you ever see is \(k\), then your estimate is then simply \(2^k\).

Theoretically speaking, this algorithm is ridiculously efficient. To keep track of \(N\) items, you merely need to store a single number that is about \(\log N\) in magnitude. And to store that single number requires \(\log \log N\) bits. (Hence, the name LogLog!)

Practically speaking, this is a very noisy estimate. You might have seen an unusually large or small number of leading zeros, and the resulting estimate would be off by a factor of two for each extra or missing leading zero.

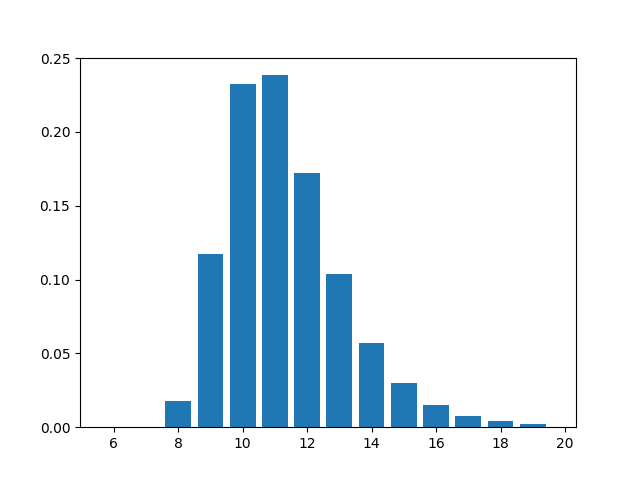

This is a plot of probability of having x leading zeros, with 1024 distinct items. You can see that the probability peaks at around x = 10, as expected - but the distribution is quite wide, with x = 9, 11 or 12 being at least half as likely as x = 10. (The distribution peaks 0.5 units higher than expected, so this implies that \(2^k\) will overshoot by a factor of \(2^{0.5}\), or about 1.4. This shows up as a correction factor later.)

That the distribution tends to skew to the right side is even more troublesome, since we’re going to be exponentiating \(k\), accentuating those errors.

To reduce the error, the obvious next step is to take an average. By averaging the estimates given by many different hash functions, you can obtain a more accurate \(k\), and hence a more reliable estimate of \(N\).

The problem with this is that hash functions are expensive to compute, and to find many hash functions whose output is pairwise independent is difficult. To get around these problems, LogLog uses a trick which is one of the most ingenious I’ve ever seen, effectively turning one hash function into many.

The trick is as follows: let’s say that the hash function outputs 32 bits. Then, split up those bits as 5 + 27. Use the first 5 bits to decide which of \(2^5 = 32\) buckets you’ll use. Use the remaining 27 bits as the actual hash function. From one 32-bit hash function, you end up with one of 32 27-bit hash functions. (The 5 + 27 split can be fiddled with, but for the purposes of this essay I’ll use 5 + 27.)

Applied to LogLog, this means that your \(N\) items are randomly assigned to one of 32 disjoint subsets, and you can keep 32 separate max-leading-zero tallies. The maximum number of leading zeros you can detect will drop from 32 to 27, but this isn’t that big of a deal, as you can always switch to a 64-bit hash function if you really need to handle large cardinalities.

The final LogLog algorithm is then:

- hash each item.

- use the first 5 bits of the hash to decide which of 32 buckets to use

- use the remaining 27 bits of the hash to update the max-leading-zeros count for that bucket

- average the max leading zeros seen in each bucket to get \(k\)

- return an estimate of \(32 \alpha \cdot 2^k\), where \(\alpha \approx 0.7\) is a correction factor

HyperLogLog

HyperLogLog improves on LogLog in two primary ways. First, it uses a harmonic mean when combining the 32 buckets. This reduces the impact of unusually high max-leading-zero counts. Second, it makes corrections for two extreme cases - the small end, when not all of the 32 buckets are occupied, and the large end, when hash collisions cause underestimates. These corrections are accomplished using ideas from Linear Counting.

The original LogLog algorithm first applies the arithmetic mean to \(k_i\), then exponentiates the mean, which ends up being the same as taking the geometric mean of \(2^{k_i}\). (\(k_i\) is the max-leading-zeros count for bucket \(i\).) HyperLogLog instead takes the harmonic mean of \(2^{k_i}\). The last two steps of LogLog are changed as follows:

- take the harmonic mean \(HM = \frac{32}{\Sigma 2^{-k_i}}\), over each bucket’s count \(k_i\).

- return an estimate \(E = 32 \alpha \cdot HM\)

The harmonic mean tends to ignore numbers as they go to infinity: 2 = HM(2, 2) = HM(1.5, 3) = HM(1.2, 6) = HM(1, infinity). So in this sense it’s a good way to discount the effects of exponentiating a noisy number. I don’t know if it’s the “right” way, or whether it’s merely good enough. Either way, it constricts the error bounds by about 25%.

Bucketing helps LogLog get more accurate estimates, but it does come with a drawback - what if a bucket is untouched? Take the edge case with 0 items. The estimate should be 0, but is instead \(32\alpha\), because the best guess for “max leading zeros = 0” is “1 item in that bucket”.

We can fix this by saying, “if there are buckets with max-leading-zero count = 0, then return the number of buckets with positive max-leading-zero count”. That sounds reasonable, but what if some buckets are untouched, and other buckets are touched twice? That sounds awfully similar to the Linear Counting problem!

Recall that Linear Counting used a hash table, with each slot being a single bit, and that there was a formula to compensate for hash collisions, based on the percent of occupied slots. In this case, each of the 32 buckets can be considered a slot, with a positive leading zero count indicating an occupied slot.

The revised algorithm merely appends a new step:

- if the estimate E is less than \(2.5 \cdot 32\) and there are buckets with max-leading-zero count of zero, then instead return \(-32 \cdot \log(V/32)\), where V is the number of buckets with max-leading-zero count = 0.

The threshold of 2.5x comes from the recommended load factor for Linear Counting.

At the other extremum, when the number of unique items starts to approach \(2^{32}\), the range of the hash function, then collisions start becoming significant. How can we model the expected number of collisions? Well, Linear Counting makes another appearance! This time, the hash table is of size \(2^{32}\), with \(E\) slots occupied. After compensating for collisions, the true number of unique elements is \(2^{32}\log(1 - E/2^{32})\). When \(E \ll 2^{32}\), this expression simplifies to simply \(E\). This correction is not as interesting because if you are playing around the upper limits of 32-bit hash functions, then you should probably just switch to a 64-bit hash function.

The final HyperLogLog algorithm is as follows:

- hash each item.

- use the first 5 bits of the hash to decide which of 32 buckets to use

- use the remaining 27 bits of the hash to update the max-leading-zeros count for that bucket

- take the harmonic mean \(HM = \frac{32}{\Sigma 2^{-k_i}}\), over each bucket’s count \(k_i\).

- let \(E = 32 \alpha \cdot HM\)

- if \(E < 2.5 \cdot 32\) and number of buckets with zero count V > 0: return \(-32 \cdot \log(V/32)\)

- else if \(E > 2^{32}/30\) : return \(-2^{32}\log(1 - E/2^{32})\)

- else: return E

Distributing HyperLogLog

Distributing HyperLogLog is trivial. If your items are spread across multiple machines, then have each machine calculate the max-leading-zero bucket counts for the items on that machine. Then, combine the bucket counts by taking the maximum value for each bucket, and continue with the combined buckets.

References

- Whang et al - A Linear-Time Probabilistic Counting Algorithm for Database Applications

- Flajolet et al - HyperLogLog: the analysis of a near-optimal cardinality estimation algorithm

- Heule, Nunkesser, Hall - HyperLogLog in Practice: Algorithmic Engineering of a State of The Art Cardinality Estimation Algorithm