Notes on Musical Notation

Originally posted 2016-12-28

Tagged: music

Obligatory disclaimer: all opinions are mine and not of my employer

I love video game music. I also love playing piano, especially classical music. So it’s only natural that I’ve tried to find sheet music for some of my favorite video game music. It exists, but unfortunately it tends not to be done very well. Typically, the notes aren’t all correct, but even if they are, they’re often notated improperly. Music notation is intricate enough that you need years of experience to internalize the patterns in the notes.

Here are some notes on common notation mistakes I see in transcriptions. As you’ll see, properly executed music notation is very dense with semantic information.

I’ll assume you have a rudimentary understanding of music notation (treble and bass clefs, note durations, accidentals) and scales/circle of fifths.

Properly indicating voice leading

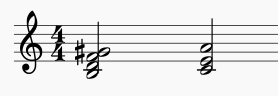

Voice leading is the movement of “voices”, or individual notes, within a chord. For example, in this two chord progression, the B resolves upwards to a C, and the F resolves downwards to an E. The musical tension generated by the B-F tritone turns into a C-E major third consonance.

When notating music, you should always follow this rule: sharps resolve upwards, and flats resolve downwards! If your name is not Maurice Ravel and you find yourself applying a sharp, and then immediately cancelling it with a natural, then you’ve probably made a mistake.

When operating in a key signature that already has many flats or sharps, never make use of alternate notes that happen to spell the same. If you need to sharp an F sharp, then you write F double sharp, not G natural. Same goes for notes that are only half-steps apart. If you need to sharp a B, then you write B sharp, not C natural.

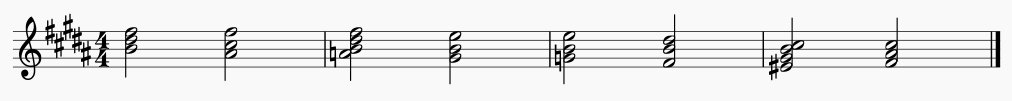

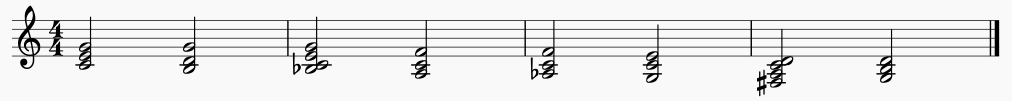

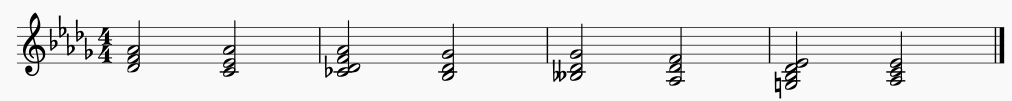

In this chord progression, flats are used when the note resolves downwards, and sharps are used when the note resolves upwards. The same chord progression is shown in B, C, and Db major, so that you can see how accidentals interact with existing key signatures.

Diminished 7th chords tend to be full of accidentals, and the correct choice of how to write them depends on how that diminished 7th chord resolves.

When done properly, an experienced musician will subconsciously make use of the information contained within the choice of accidentals to predict the chord that comes next. When this expectation is violated, it instead leaves a sense that something is not quite right.

To get some more practice, I’d recommend analyzing Beethoven’s Moonlight sonata. You’ll see that every accidental resolves in the direction it is expected to.

Adding reminder accidentals

The official rule is that accidentals are reset with every new bar of music. But often, you’ll see a note redundantly labelled with an accidental, to remind you that an accidental from a previous measure is no longer in effect. This is okay and even encouraged.

Respecting voices

Traditionally, piano music is written on two staffs. Normally, these two staffs are thought of as “left hand” and “right hand”. This is often true for simple music, but in general this is the wrong way to think about it. Instead, think of the two staffs as a playground for different voices to move around on. There may be many voices, and the pianist decides which hand will play each voice. It is more important for music notation to capture the intent of the music, than it is to recommend a division of the notes between left and right hands.

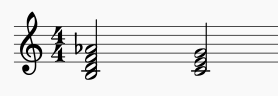

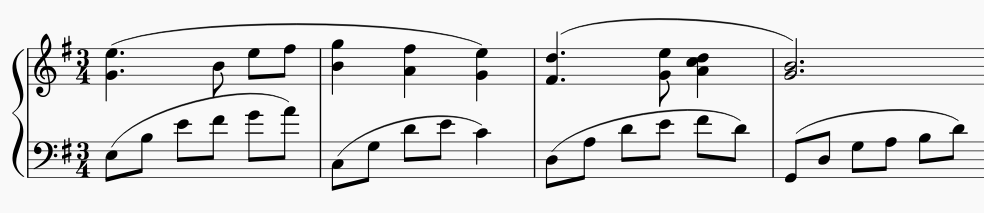

For example, this excerpt from a transcription of To Zanarkand is incorrect, because the first measure implies that the lower voice suddenly stops, while the upper voice suddenly picks up some harmonization.

Instead, this reworked version leaves both voices intact, and adds some phrasing for good measure.

When a voice transitions across staffs, cross-staff beams should be used as appropriate. It’s up to the editor to decide what placement of notes on ledger lines will result in the least visual clutter.

Using the Moonlight Sonata again as an example, we have three voices: the lower base line, the undulating middle voice, and the upper melody voice. You’ll see in the sheet music that the middle voice jumps around the staffs as is convenient, even though in practice, the middle voice is always played by the right hand. And whenever the melody happens to fall on the bass clef, the treble clef does not get a rest mark - since after all, the melody isn’t resting!

Respecting the beat

Occasionally your music will be syncopated, and the notes will fall off-beat, instead of on beat. In such cases, your musical notation must still respect the beat!

In Beethoven’s Appassionata (timestamp 0:51), we have a sequence of quarter notes in the right hand, notated using a row of quarter notes. So far, so good. But the left hand also consists of a sequence of quarter notes - but every third quarter note is spliced into two eight notes, and then tied back together again. What gives?

The answer is that the time signature is 12/8, so we have four beats each consisting of three eighth notes. By splitting up the left hand’s quarter notes, their relationship to the beat of the music is emphasized. This split-tied notation is in fact easier for me to read than the alternative.

If your music has syncopation, don’t let the notated music lose sight of the beat! If you ignore the beat, then it generates a lot of confusion when it comes to sightreading the music.