The Sulfur Untethering

Originally posted 2022-07-09

Tagged: chemistry, sustainability

Obligatory disclaimer: all opinions are mine and not of my employer

Sulfur economics is a bit unusual in that its market supply is untethered from demand. How is this possible? In a nutshell: the Clean Air Act.

Much of this material is summarized from this 2002 USGS report.

Sulfur production and the Frasch Crash

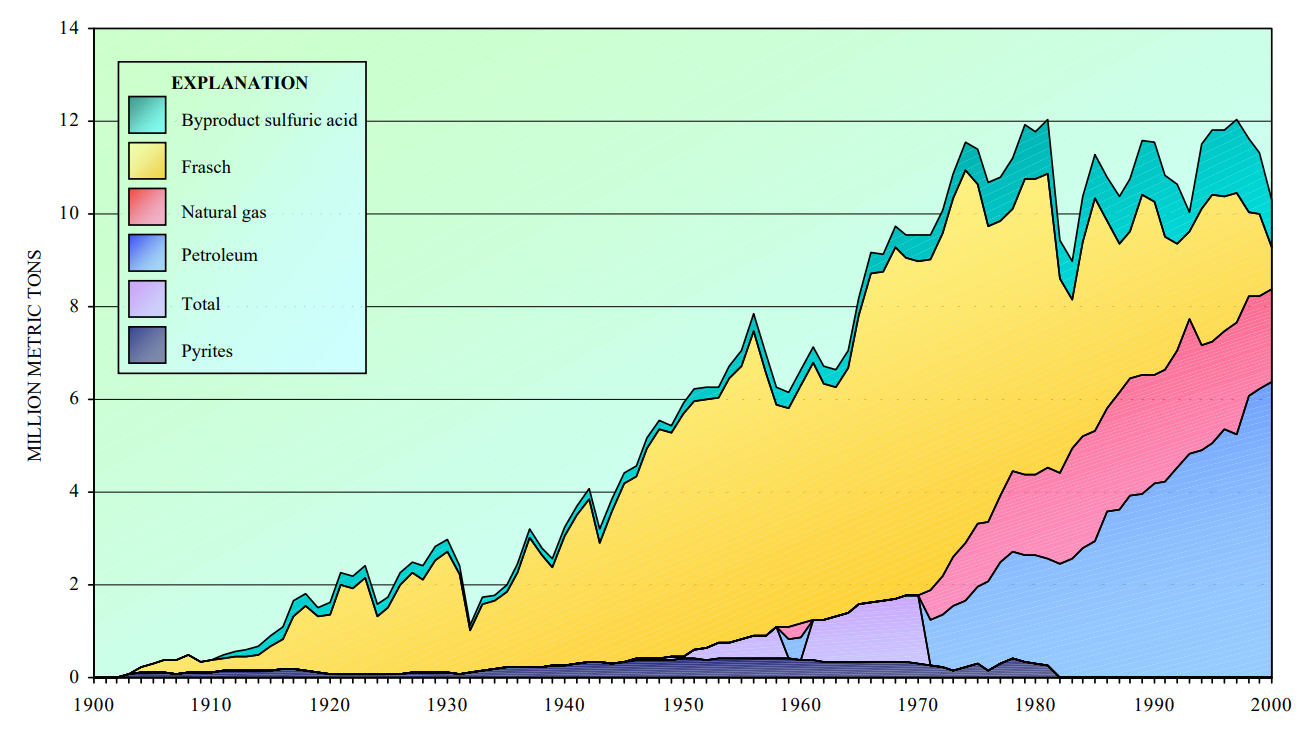

Throughout the 20th century, the vast majority of sulfur was mined by the Frasch process, in which underground sulfur deposits are melted with superheated water, and pumped back up to the surface. Around 2000, the last Frasch mine in the U.S. shut down. It was simply not competitive anymore, despite being the cheapest way to produce sulfur.

The culprit behind the Frasch crash was the 1990 Clean Air Act. All fossil fuels contain some sulfur, and when burned, the sulfur turns into \(\ce{SO2(g)}\) in the atmosphere and returns to the earth as acid rain. The Clean Air Act created a cap-and-trade program to limit sulfur emissions. Nowadays, fossil fuels have upwards of 97% of their sulfur content stripped during refining. This forces the petroleum industry to produce sulfur in quantities untethered to the demand for sulfur.

Given the size of the petroleum industry, sulfur stockpiles continued to grow, and peaked in 2003, despite the shutdown of every Frasch mine. Eventually, usage caught up and the stockpiles were drawn down, causing a price spike in 2008. Given sulfur’s ties to the petroleum industry, you won’t be surprised to learn that there’s currently another sulfur price spike due to the war in Ukraine.

Sulfur’s uses and contributions to ocean acidification

What is sulfur used for, anyway? Elemental sulfur is used in rubber (see Vulcanization), but the vast majority is converted into sulfuric acid, to be used for its acidic properties. Eventually, this sulfuric acid finds its way to the ocean, where it causes a net efflux of carbon dioxide. Each atom of sulfur results in the efflux of 2 atoms of carbon.

\[ \begin{align*} \ce{S + 3/2O2 &-> SO3(g)} \\ \ce{SO3(g) + H2O &-> H2SO4} \\ \ce{H2SO4 + 2HCO3- &-> SO4^2- + 2H2O + 2CO2(g)} \end{align*} \]

This equation tells us that 1 mol (32g) of sulfur triggers 2 moles (24g C, 88g \(\ce{CO2}\)) of outgassing. Humans extract roughly 80 megatons of sulfur a year, so to a first approximation, about 220 MT \(\ce{CO2}\) are indirectly added to the atmosphere by the sulfur industry, about 0.8% of total anthropogenic carbon emissions. Actually, the impact is not quite as bad as 220 MT of carbon. About a half of our sulfuric acid usage is used to extract phosphate and copper oxide ores, which are net alkaline. The result is accelerated weathering and net neutralization of sulfuric acid, when used for phosphate/copper extraction. Thus, the sulfur industry’s net contribution to ocean acidity is about half the previous number, about 110 MT \(\ce{CO2}\), or 0.4% of anthropogenic emissions.

The impact of this acidification is quite local, because sulfuric acid is very water-soluble and collects via acid rain -> river runoff. Acidification from sulfur usage primarily affects rivers and coastal regions, and directly causes coral reef destruction.

(A funny and depressing aside: the byproduct of sulfuric acid mining of phosphate rock is calcium sulfate, or gypsum. Most of this mining happens in Florida, which also happens to have mildly radioactive phosphate ore. Thus, while gypsum would otherwise be used to make drywall, the radioactivity leads to massive, massive piles of unusable gypsum byproduct in Florida, to the tune of 1 billion tons of phosphogypsum. It’s okay, Florida will be underwater soon enough!)

Economic and climate implications of sulfur

The sulfur economy exists in two possible modes, due to its ties to the petroleum industry. Depending on the clearing price of sulfur, Frasch mining is either commercially viable or not; we are currently in a nonviable regime.

Ultimately, the vast majority of sulfur atoms removed from the ground will turn into sulfuric acid and contribute to outgassing of \(\ce{CO2}\). So, taking the petroleum industry as a constant, we should instead seek to reduce the demand for sulfuric acid, making Frasch mining commercially unviable.

Ocean alkalinity seem to have very welcome positive externalities on the sulfur market. Electrolysis is used to create a pH gradient and create acid/base streams. The alkaline base stream is dumped in the ocean, counteracting the effect of sulfuric acid runoff. The acid stream is awkward, because if it finds its way back to the ocean, it would be futile - kind of like trying to cool a house by leaving the refrigerator open. My assertion is that if we can concentrate the acid stream to industrially useful levels, it would displace the use of sulfuric acid, and in turn reduce the efflux of \(\ce{CO2}\) due to sulfuric acid. In this scenario, it doesn’t matter if the acid finds its way back to the ocean, because it has reduced the extraction of sulfur elsewhere in the economy.

Conclusion

While the sulfur economy is a small part of the overall anthropogenic carbon problem, its effects are disproportionately localized and we would be likely to see immediate environmental impact in the form of coastal habitat restoration. Given that sulfuric acid is primarily useful for its acidic properties, there are undoubtedly ways to replace its usage with other net-neutral acid sources. This would reduce \(\ce{CO2}\) efflux from the ocean and is morally equivalent to direct air capture.